Tales from Accounting's Digital Revolution

When you think of accounting, you probably think of a staid profession. Of old men in dusty offices and nothing ever changing. You might also think of an industry ripe for AI disruption, with millions of people only waiting to get replaced.

But accounting went through a digital revolution before. In 1950s to early 2000s, accounting transformed from paper and abacus to a completely computerized profession. Millions of people had to completely re-imagine their craft, billion dollar companies rose and fell and trillions of dollars of value were created. The resulting change led to consolidation which leaves almost all large corporations dependent on just 4 accounting firms.

There is many stories to be told, in this edition I will focus on the individual pioneers who played a large role in the revolution.

The Mainframe Pioneers: Betting Everything on Electronic Dreams (1950s-1970s)

Joseph Glickauf’s missionary zeal launched the computer consulting industry

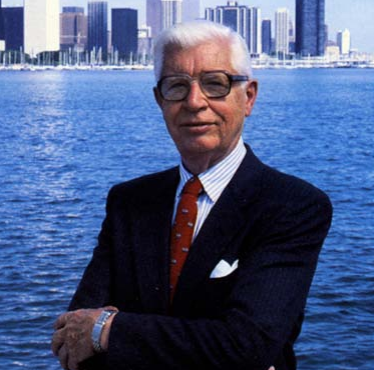

The story begins with Joseph Simon Glickauf Jr., a South Side Chicago native whose Navy service in the Research Division of the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts prepared him to recognize revolutionary potential where others saw expensive curiosities. Hired by Arthur Andersen in 1946 specifically to investigate electronic computers, Glickauf visited early computing demonstrations in Philadelphia and returned with evangelical fervor.

“The demonstration we were given was impressive, if brief,” Glickauf later wrote. “But it took no genius to see that we had before us a device that would outrun, outpower and outmode every device that preceded it. I left Philadelphia with a mission. It was to convince everyone I encountered…that this day, I had indeed seen a vision of what would soon become a revolutionary reality.”

Knowing that skeptical accountants needed tangible proof, Glickauf built his famous “Glickiac”—a small-scale electronic counting machine that could perform 600 calculations per second. During demonstrations at regional offices, he would challenge auditors to count along with the flashing lights, then gradually increase the speed until human comprehension failed. “The neon lights were flashing and you couldn’t even see them—and pretty soon, it was far beyond the speed that anyone could possibly count,” one observer recalled. “But it was a very vivid demonstration.”

The January 1951 Glickiac demonstration proved powerful enough to convince Arthur Andersen partners to commit whatever resources necessary to enter computer consulting before competitors. This decision launched what would become a multi-billion dollar industry, but the early implementation was anything but smooth.

Leonard Spacek’s vision and the GE disaster that taught humility

Leonard Paul Spacek, Arthur Andersen’s managing partner, brought both vision and hard-earned pragmatism to the computerization effort. Born to Czech immigrants in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Spacek experienced childhood poverty when his mother’s illness forced the family to split up. Local farm families took him in, and he worked for room and board while finishing high school—experiences that instilled the work ethic and determination that would later drive his leadership of Arthur Andersen.

When Arthur Andersen died in 1947, partners initially voted to dissolve the firm. Spacek, at age 41, led the effort to save it and was described as being “on the cutting edge of new technologies, especially computers” with “a sense of marketing before the term was even coined.” Under his leadership, Arthur Andersen grew from $6 million in annual revenue in 1947 to $65 million by 1965.

The General Electric project became both Arthur Andersen’s greatest early triumph and most humbling lesson. In 1952, they won a $64,000 feasibility study for GE’s Appliance Park in Louisville, Kentucky. Glickauf recommended the UNIVAC I over IBM equipment, noting that “IBM did not have equipment that was available at the time that GE wanted to start. IBM was a latecomer in the [electronic computer] field.”

The initial implementation was disastrous. “When we first started off, we thought this was a machine that could run a payroll the size of GE’s at that time—10,000 employees—in two hours,” Glickauf recalled. “As it turned out, at the end of 40 hours (the first time it was programmed), it still hadn’t completed a payroll.”

Glickauf had to return “hat in hand” to GE, admitting “We have to redo it.” It wasn’t until late 1956 that the payroll system actually worked effectively. This painful experience taught the fledgling computer consulting industry that promises were easy to make but far harder to deliver.

The physical and cultural reality of mainframe computing

Working with early mainframes was a profoundly different experience from modern computing. The UNIVAC I was a 30-ton machine with over 5,000 glass vacuum tubes that cost $1.2 million (approximately $14 million today). Technicians could literally “step inside the UNIVAC 1 to make repairs.” The massive machines filled entire rooms and required specialized air conditioning and power systems.

“The first programmers didn’t have an easy time of it,” one contemporary noted. “As the old joke goes, ‘all they had were ones and zeros, and sometimes they didn’t even have the ones’… the system was arcane, debugging tools were non-existent and computer languages had yet to be invented.”

The cultural impact within Arthur Andersen was equally profound. Employees began referring to themselves as “Arthur’ Androids” due to the firm’s emphasis on uniform methods and appearance—standardization that proved crucial for implementing computer systems consistently across offices. The firm invested 15-20% of net revenue in professional development, creating what was ranked the #1 corporate training program. This massive investment was essential for transitioning staff from manual to computerized methods.

Nancy Bagranoff from GE to president of the American Accounting Association

General Electric was a major training ground for the next generation of accounting technology pioneers. Nancy Braganoff started her career at GE’s Financial Management Training Program before moving into Academia. After her doctorate, she became one of the leading figures in the field of accounting information systems, publishing serveral core textbooks on the topic

In 2009 she was elected president of the American Accounting Association. Academic work like hers laid the foundation on which later iterations of technology were built.

The Personal Computer Revolution: Spreadsheets Transform Everything (1980s)

Dan Bricklin’s Harvard frustration births the killer app

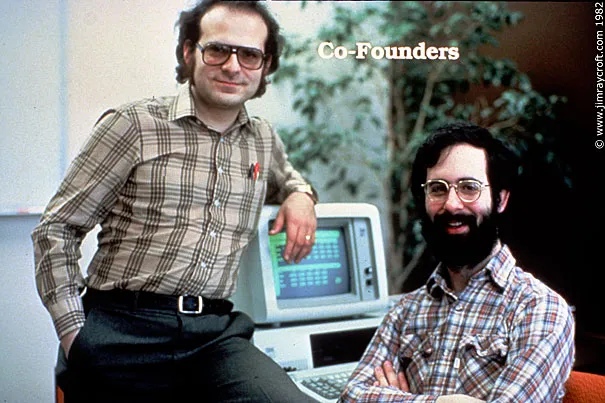

The next chapter begins with a frustrated MBA student at Harvard Business School. Dan Bricklin, born July 16, 1951, in Philadelphia, had earned his electrical engineering and computer science degree from MIT in 1973 and worked at Digital Equipment Corporation before entering Harvard Business School in the late 1970s.

The eureka moment came during his Harvard studies. “In business school I used the DEC system when I needed to write a little BASIC program to help me with my homework,” Bricklin recalled in a 1986 interview. “But it wasn’t fast enough. Even if it only took me 15 or 20 minutes to throw together a little program to do the analysis we wanted for a group project, that wasn’t fast enough, and the program usually had bugs. That’s when I came up with the idea for VisiCalc, putting together the immediacy of word processing and the fluidity of the screen.”

His original vision was remarkably futuristic: “The original design was futuristic. I would have my hand on my calculator and the calculator would have a ball on the bottom of it, like a mouse, so you could move it around to position the cursor on the screen. It had the number key pad right there so you wouldn’t even have to take your hand off in order to do a calculation. I wanted to implement a head-up display, as with a fighter plane where you see the numbers in front of you.”

Bricklin’s Harvard professors were encouraging but challenging. His production professor told him: “You know, the type of stuff you’re talking about, people do on blackboards now when they do production planning. And sometimes they have blackboards that stretch the length of two rooms.” Professor Barbara Jackson pushed him further: “Look, if you want to get a chairman of the board of a company to do something, it’s got to be really simple. This is getting close, but it’s not there yet.”

Bob Frankston’s technical wizardry and unconventional partnership

Working with his MIT classmate Bob Frankston, they developed VisiCalc using an unusual schedule. “Bob would write the code at night when time sharing was cheap,” Bricklin described. “He’d get up around 3:00 in the afternoon, when I would come back from school. We’d go over what he did to the program; I’d test the program, figure out how to do new features, interview accountants, and do other startup procedures… He’d work until morning, when he’d go to sleep.”

Frankston brought crucial technical expertise to the partnership. “At that time an Apple II had 16KB of memory – about one billionth the capacity of today’s machines. So instead we paid for time on MIT’s Multics system,” he recalled. When asked about VisiCalc’s importance, Frankston reflected: “Of course I felt very good about it but it also made me aware of the importance of happenstance such as meeting Dan in the process. VisiCalc happened to be at the leverage point of doing calculations vs. the a more general problem such as word processing.”

VisiCalc launched in April 1979 for the Apple II. “It got good reviews from a few people. Most of the magazines ignored it. It wasn’t written up in some of the magazines for about a year,” Bricklin noted. But the business impact was immediate and profound. Steve Jobs famously credited VisiCalc with “propelling the Apple II to the success it achieved more than any other single event.” Harvard Business School Alumni

When asked about VisiCalc being called the first “killer app,” Bricklin responded emotionally: “Very happy! As a child during the 1960’s, the idea of changing the world for the better was something you’d strive for. To actually accomplish it is great. It also takes off any pressure when you wonder whether or not you will accomplish something you can be proud of in life.”

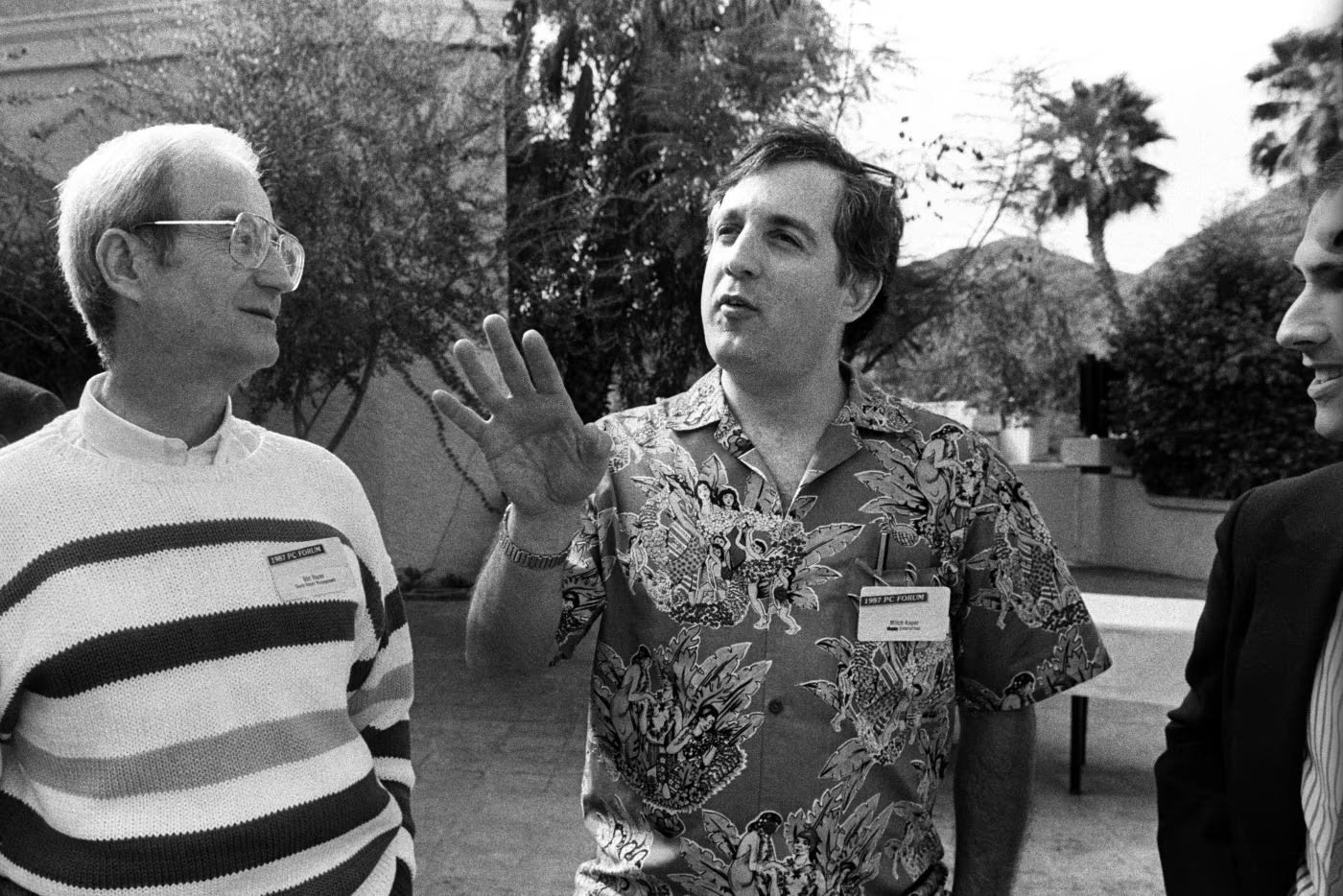

Mitch Kapor’s Hawaiian shirt disrupts IBM’s buttoned-up culture

Mitchell David Kapor, born November 1, 1950, in Brooklyn and raised in Freeport, Long Island, brought a counterculture sensibility to business software. After earning a B.A. from Yale College in 1971 in psychology, linguistics, and computer science, he worked as a product manager for VisiCalc before leaving VisiCorp to start his own venture.

In 1982, Kapor founded Lotus Development Corporation with Jonathan Sachs and backing from venture capitalist Ben Rosen. Their vision was to create something far superior to VisiCalc.“They [Bricklin and Frankston] had a very weak entrant for that machine that didn’t take advantage of the IBM PC… people wanted to build large spreadsheets and they couldn’t. The VisiCalc for PC was hard to use. I said: ‘Let’s build something that really takes advantage of these capabilities’.”

Kapor’s philosophy was fundamentally different: “I felt the key to unlocking the market was making something ordinary people could use. It had to be better than single-letter commands.”

His personal style was legendary. Bill Aulet from MIT recalled when Kapor visited IBM in 1982: “Kapor arrived dressed not in the IBM standard of a suit and tie but in a Hawaiian shirt… This guy was so cool, so relatable.”

The results were unprecedented. Lotus 1-2-3 launched on January 26, 1983, integrating spreadsheet, graphics, and database functions. “Kapor in 1982 had forecast first-year sales for 1-2-3 of $3 to $4m based on the performance of Personal Software… 1-2-3 made $53m in year one, selling at $495 per a copy on a PC bundle of the day that was priced $5,000. ‘We had no idea - nobody had put out software like that before,’ Kapor said of his sales estimates.”

Lotus became the world’s third-largest microcomputer software company in 1983 with $53 million in sales in its first year, compared to their business plan forecast of just $1 million.

Roman Kepczyk lives the transition as “the computer guy”

While software pioneers created the tools, individual accountants lived through the daily reality of transformation. Roman Kepczyk, CPA, provides the most comprehensive first-hand account of this transition. In January 1986, he joined a regional CPA firm in Arizona “right in the midst of their transition from manual processing and IBM36/AS400 mainframe computers to personal computers.”

“Using a personal computer for accounting work was on the ‘bleeding edge’ in 1986,” Kepczyk recalled. “Most accountants were still working on multi-column paper pads, totaling numbers with a ten-key and using external data processing centers for tax return and general ledger preparation.”

As the lowest-ranking staff member with Wang microcomputer experience, he was tasked with unboxing and setting up the firm’s new personal computers, eventually becoming “the computer guy” within the firm. “I jumped into my first busy season by reconciling bank statements and general ledgers via a standalone spreadsheet program called SuperCalc (precursor to Lotus 123 and today’s Excel).” His technological expertise led to the firm creating a “Microcomputer Consulting” practice, supporting applications like CYMA Shoebox, DacEasy, Peachtree, and QuickBooks. After six years, he was made partner and tasked with overseeing the firm’s IT—a career trajectory that would have been impossible just a decade earlier.

Ben Dyer invents an industry from Peachtree Street

Ben Dyer’s journey began in downtown Atlanta, where he joined four electrical engineers from Georgia Tech who had opened one of the first computer stores in the country, selling the Altair 8800 microcomputer. “They needed someone like me,” Dyer said. “None of them had any business experience at all. I joined them and just had a blast inventing an industry there. I got to deal with what I call the pioneering customers who made our industry possible.”

In 1978, when the company needed to choose between expanding computer retail or focusing on software development, they split on Labor Day. Dyer became president and founder of the software division. The name “Peachtree” came from an expensive PR consultant who visited their Peachtree Street offices and suggested naming the company after the street. “Outside of Atlanta it was a really good brand name,” Dyer noted wryly, referencing Atlanta’s numerous Peachtree Streets.

The educational challenge was enormous. **“Our dealer plan […] gave us Tier 1 support out on the field. At least we were able to handle all the first line questions like, ‘What’s a credit or a debit?’ A lot of people didn’t understand accounting, so we ended up providing accounting education as much as computer support.”**

At the 1980 COMDEX expo, IBM executives approached Dyer wanting to license Peachtree Software for the new IBM PC. Shortly before the IBM PC’s August 1981 debut, Management Science America (MSA), hearing that Peachtree would be included in the IBM PC launch, acquired the company.

Caroline Olsen’s rise and fall alongside Peachtree

The spread of accounting software created immense demand for people who knew how to use it. Along the giants like Andersen, countless smaller businesses sprang up to serve the need.

Caroline Olsen used her knowledge of Peachtree to jump into entrepreneurship. She had used the software at a previous employer and set up her own small consulting business around it. “I would make a small profit from the software package, but the real money would be in the installation and in teaching employees how to use it. I lived in a rural area back then, and my first client was an excavation company.”

The small business grew through word of mouth and Caroline quickly had a base of customers in her area. Next to the one time installation she would also provide ongoing support to people with accounting problems.

Eventually, the easier software rendered her services obsolete. “QuickBooks was taking over the marketplace, so most of my former clients converted to it because of its user-friendly applications and lower cost. I read that Peachtree was bought by Sage Intact, which advertises that it is better than “limited” QuickBooks. At this point in my life, I don’t care.”

The Small Business Software Revolution: Kitchen Tables to Billion-Dollar Deals (1990s-2000s)

Scott Cook transforms a domestic complaint into democratized accounting

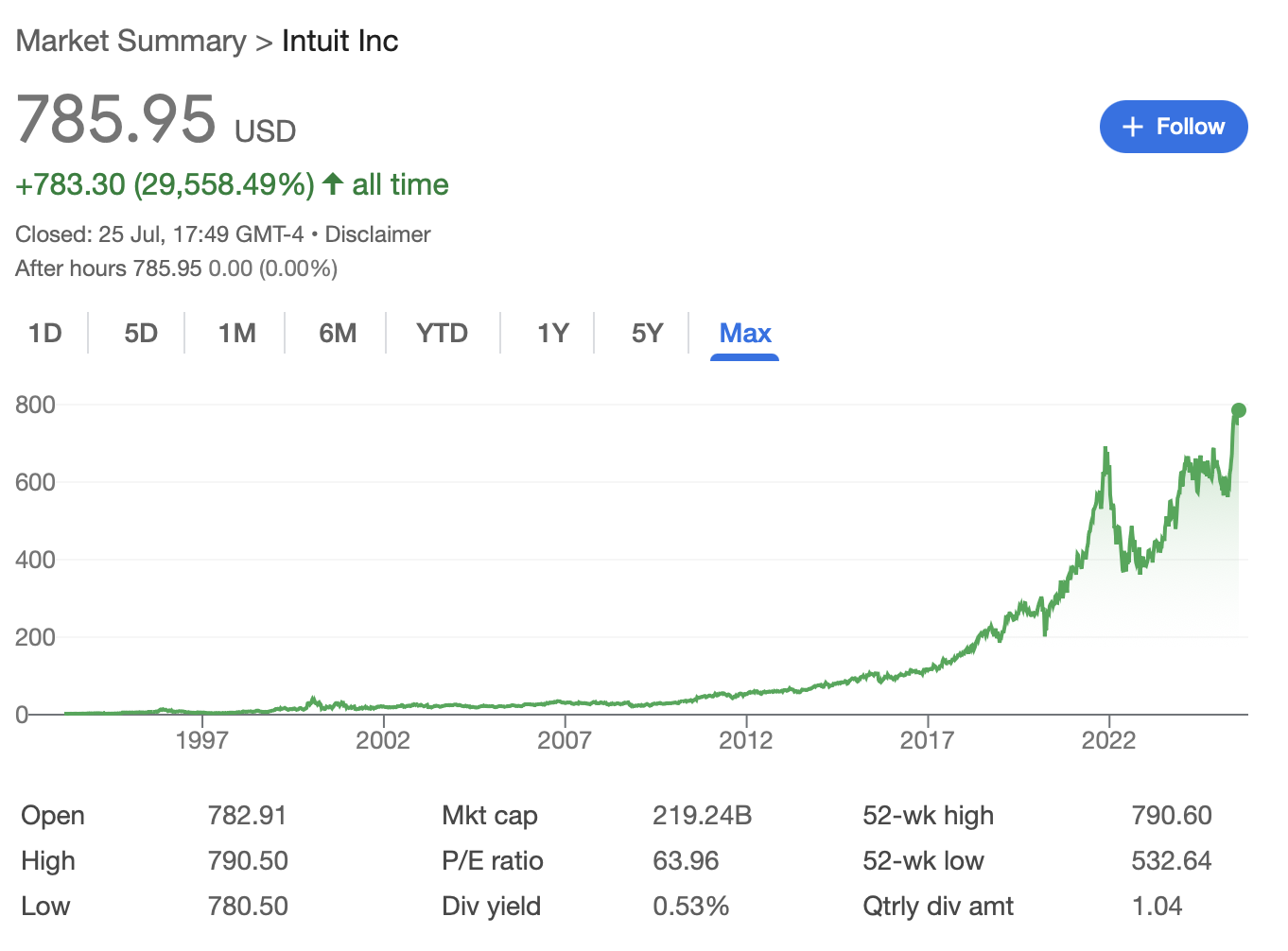

The most transformative personal story of business software begins with a simple domestic complaint in 1982. Scott Cook’s wife, Signe Ostby, was paying bills at their kitchen table and complained about the tedium of the process. This “ordinary, everyday moment” would eventually generate Intuit, Inc., now worth $130 billion.

Cook, armed with brand management experience from Procter & Gamble as well as Bain, co-founded Intuit in 1983 with Stanford computer science student Tom Proulx. Frederick Cook’s vision was clear: “create software that anyone could use without technical expertise.”

The early years were brutal. “We talked to over two dozen venture firms, and not a single firm believed that people would buy a computer for their homes, or didn’t believe they’d do their checkbook on it. And even if that happened, they didn’t believe they’d buy from us,” Cook recalled. They hoped for $2 million in marketing funds but only secured $151,000 in angel money.

Success came through obsessive customer focus. “The business switched to tripling every year, just on that one product [Quicken] triple—then another triple, and then another triple,” Cook said. What drove the success was customer word of mouth.

When Cook noticed small businesses using personal Quicken software in their offices, he realized: “We assumed the paradigm was, of course, they all used accounting [software]. No, they hate accounting.” This insight led to QuickBooks in 1991, which Cook positioned as “the first accounting software with no accounting in it.” The company outsold competition within two months.

Cook’s philosophy centered on making complex systems simple. He emphasized: “If you want a big business, solve a big problem” and advocated for “savoring surprises”—understanding unexpected customer behaviors that reveal new opportunities.

Doug Burgum bets the family farm on Great Plains Software

Doug Burgum’s pivotal moment came as a 26-year-old consultant at McKinsey & Company in Chicago. After spending grueling nights with an HP-12C calculator, a colleague showed him VisiCalc running on an Apple II. “I had just spent four hours doing what that thing did in a minute. It was one of those blow-you-away kind of moments,” Burgum recalled. “People say, ‘He was a visionary.’ Well, it’s not hard to have vision when you get hit in the head with a two-by-four.”

When Great Plains Software founders Joe Larson and Roger Turner sought a marketing vice president, they found Burgum through family connections. Visiting the Fargo offices, Burgum saw orders “flying out the door” and figured business was booming. He mortgaged his Arthur, North Dakota farmland—inherited from his late father—investing $250,000, literally “betting the farm.”

Only later did he discover the “robust sales” were actually a backlog of unshipped orders. “I didn’t do all the best due diligence that I could have,” he admitted.

Burgum transformed Great Plains into a service-focused company, drawing on his family’s grain elevator business values: “In a grain elevator, if you piss off somebody, it might be three generations before you get that customer back.”

The company developed distinctive practices: premium service guarantees (they went 402 days without missing a support deadline), customers were always called “Customers” and vendors “Partners” (with capital letters), and at events, employees couldn’t sit or eat until customers were served first. Burgum once cracked an egg on his head at a company event to show contrition after a buggy product release.

“It was a party-fest, in a way,” recalled Diana Wilberscheid. “You worked your butt off, and then every night everybody went out to Chub’s Pub.” The company grew from 50 employees in 1984 to 300 by 1990, doing $22 million in annual sales. Great Plains was named one of Fortune’s “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” in 1993—the smallest company ever to receive the honor.

In 2001, Burgum’s Stanford classmate Steve Ballmer, now Microsoft CEO, called wanting to make a deal. Microsoft acquired Great Plains for $1.1 billion, at the time Microsoft’s largest acquisition ever.

Until next time friends

And this is where the tales end for today. Of course, there is more to be said. How Microsoft Excel came to dominate. How Arthur Andersen helped cause the greatest corporate scandal of all time. How 4 companies consolidated accounting and auditing for all major businesses. And how, despite all the automation, the number of accountants in the US almost doubled.

But that is for another time. If you enjoyed this article, send it to a friend. Thanks for reading!